How VPNs Work: Security, Encryption, and Use Cases

A VPN (Virtual Private Network) creates an encrypted “tunnel” between your device and a VPN server, reducing eavesdropping risk on untrusted networks, masking your IP address from the sites you visit, and enabling secure access to private resources. This article breaks down the moving parts—protocols, encryption, authentication, routing, and operational realities—so you can choose and use VPNs with clear expectations.

Table of Contents

- What a VPN is (and what it isn’t)

- The core mechanics: tunneling, encryption, authentication

- VPN protocols explained (WireGuard, OpenVPN, IPsec/IKEv2)

- Security realities: what VPNs protect, and what they don’t

- Common use cases and the best VPN pattern for each

- Practical checklist: how to use VPNs safely

- Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts

- Resources

What a VPN is (and what it isn’t)

A VPN in one sentence

A VPN extends a private, encrypted connection across a public network by encapsulating your traffic inside a protected tunnel to a VPN server, then forwarding it to its destination from there—effectively shifting where your traffic “emerges” onto the internet.

VPN vs HTTPS

HTTPS (via TLS) encrypts traffic between your browser/app and a specific website or API endpoint. A VPN encrypts traffic between your device and the VPN server—covering more than just the browser (for example, other apps), but only until the VPN server. In practice:

- With HTTPS only: your local network and ISP can usually see the destination domain and some metadata, but not the encrypted content (assuming modern TLS and correct configuration).

- With a VPN: your local network and ISP see an encrypted tunnel to the VPN provider, while the sites you visit see the VPN server’s IP address (not your home IP).

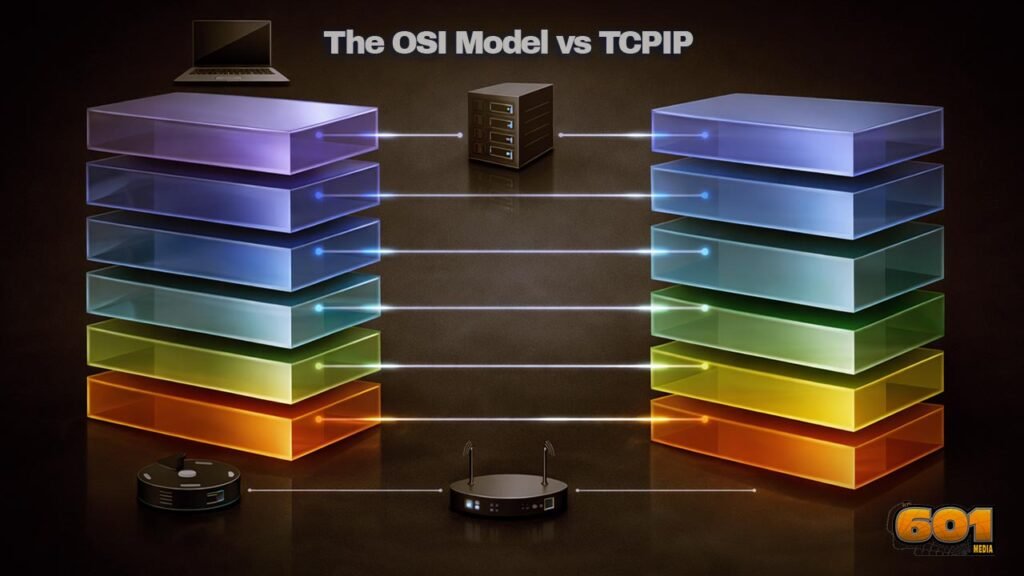

TLS is widely standardized and governed by hardening guidance such as NIST SP 800-52 for TLS implementations; VPNs rely on tunneling protocols and operational security at the provider and endpoint. NIST describes TLS as protecting data during dissemination across the internet and provides configuration guidance.

Threat models a VPN helps with

A VPN can be a strong control against certain risks, but it’s not a magic invisibility cloak. It helps most with:

- Untrusted networks: reducing eavesdropping on public Wi-Fi, hotels, airports, conferences, and shared networks.

- ISP-level tracking of your traffic patterns: your ISP sees that you connect to a VPN, but typically can’t inspect the contents inside the tunnel.

- IP-based tracking and geo-based exposure: websites see the VPN IP rather than your home IP (though browser fingerprinting can still identify you).

- Secure access to private services: connecting to internal networks, dev environments, or admin panels that should not be exposed publicly.

What it does not do (by itself):

- Prevent malware, phishing, account takeovers, or weak passwords.

- Guarantee anonymity—especially against advanced tracking or identity correlation.

- Stop the VPN provider from seeing your traffic if it chooses to log or misuse it.

The core mechanics: tunneling, encryption, authentication

Step-by-step: what happens when you turn a VPN on

At a high level, turning on a VPN triggers four core actions:

- Handshake: your device and the VPN server agree on cryptographic parameters and prove identities (or at least authenticate the server).

- Key establishment: they create shared session keys (ideally with perfect forward secrecy, so one compromised key doesn’t expose past sessions).

- Tunnel interface: your device creates a virtual network interface (a software network adapter). Apps send packets to this interface as if it were a real network link.

- Encapsulation + routing: the VPN client encrypts and encapsulates traffic and sends it to the VPN server; the server decrypts and forwards it to the destination, then returns responses back through the tunnel.

Encryption, integrity, and perfect forward secrecy

A secure VPN needs three cryptographic properties working together:

- Confidentiality: encryption prevents outsiders (e.g., someone on public Wi-Fi) from reading your traffic inside the tunnel.

- Integrity: authentication (often via AEAD modes or HMAC) prevents tampering—so an attacker can’t quietly modify your traffic in transit.

- Perfect forward secrecy (PFS): session keys are derived from ephemeral key exchanges, limiting damage if a long-term key is compromised later.

Modern protocols implement these in different ways. WireGuard, for example, uses modern cryptographic primitives (such as ChaCha20-Poly1305 for authenticated encryption and Curve25519 for key exchange), and its paper describes strong PFS properties and a design aimed at high speed and small attack surface. OpenVPN, by contrast, uses an SSL/TLS control channel for authentication and key exchange, then uses derived keys to protect the tunnel traffic—documented in its “Cryptographic Layer” notes.

Routing, DNS, and why “DNS leaks” happen

When a VPN is active, the key question is: “Which traffic goes through the tunnel?” That’s a routing decision.

- Full-tunnel: all (or nearly all) traffic routes through the VPN. This maximizes privacy from the local network but can add latency.

- Split tunneling: only selected traffic goes through the VPN (for example, corporate apps), while the rest uses the normal internet connection. This can improve speed but increases complexity and leak risk.

DNS is a special case because it can leak where you’re trying to go, even if content is encrypted. A “DNS leak” often happens when:

- The VPN client doesn’t push DNS settings correctly (or the OS ignores them in some scenarios).

- Split tunneling sends DNS outside the tunnel while web traffic goes inside.

- Multiple network adapters compete (Wi-Fi + Ethernet + virtual adapters), and the system chooses the wrong resolver.

A well-designed VPN setup routes DNS queries through the tunnel and uses resolvers that align with your privacy and policy goals.

VPN protocols explained (WireGuard, OpenVPN, IPsec/IKEv2)

WireGuard

WireGuard is a modern VPN protocol designed to be simpler to audit and fast in practice. Its design emphasizes a small codebase and a conservative set of cryptographic choices. WireGuard’s official documentation describes its use of contemporary primitives (including Curve25519 and ChaCha20-Poly1305) and the Noise framework approach, while the WireGuard paper details its handshake and encapsulation model in more academic depth.

- Where it shines: performance, simplicity, mobile friendliness, and straightforward configuration for many deployments.

- Operational note: it typically uses UDP and benefits from stable NAT traversal; roaming is generally good because it’s designed for real-world network changes.

OpenVPN

OpenVPN is a long-standing, widely deployed VPN solution. It uses SSL/TLS for authentication and key exchange, then encrypts tunnel traffic using symmetric keys derived through that secure control channel. OpenVPN’s community docs explicitly describe the multiplexing of the TLS session with the encrypted tunnel data stream and its approach to integrity protection.

- Where it shines: mature ecosystem, extensive configurability, and compatibility with many network environments.

- Operational note: it can run over UDP or TCP; TCP can help traverse restrictive networks, but “TCP-over-TCP” can degrade performance in some cases.

IPsec / IKEv2

IPsec operates at the network layer and is commonly used for site-to-site VPNs and enterprise remote access. NIST describes IPsec as a framework of open standards for protecting communications and creating VPNs, typically configured via IKE (Internet Key Exchange). NIST’s guidance on IPsec VPNs is especially relevant for enterprise designs, gateway placement, policy, and operational controls.

- Where it shines: enterprise deployments, standards-driven environments, and robust site-to-site connectivity.

- Operational note: IKEv2 is often praised for stability on mobile networks (connection resilience when switching networks), depending on implementation.

How to choose a protocol

Instead of chasing brand claims, match protocol choice to constraints:

- If performance and simplicity matter most: WireGuard is often the practical default.

- If you need maximum compatibility and knobs: OpenVPN remains a versatile tool, especially where custom TLS configurations are required.

- If you’re doing enterprise network engineering: IPsec/IKEv2 is still foundational, especially for gateway-based and site-to-site designs.

Security realities: what VPNs protect, and what they don’t

Public Wi-Fi and man-in-the-middle risk

On untrusted Wi-Fi, attackers can attempt manipulator-in-the-middle (MITM) techniques: intercepting or altering traffic between client and server. OWASP describes MITM as intercepting communications by splitting the connection and inserting the attacker in between. While modern HTTPS reduces exposure, risks still exist:

- Not all apps enforce TLS correctly in every scenario.

- Downgrade and misconfiguration issues still happen, and weak transport security can expose sessions.

- Captive portals and “evil twin” hotspots can manipulate what users click and trust.

A VPN helps by encrypting all tunnel traffic between your device and the VPN server, reducing what local attackers can see or modify in transit.

The VPN provider trust problem

A VPN shifts trust. Without a VPN, your ISP and local network operator are in a privileged position. With a VPN, your provider can occupy that privileged position for tunneled traffic. That means provider selection becomes a governance and risk-management decision:

- Logging policy vs reality: marketing “no-logs” is not the same as verified operational controls.

- Jurisdiction and legal exposure: laws and enforcement patterns vary widely.

- Security posture: audits, incident response maturity, and transparency reports matter.

From an Innovation and Technology Management perspective, the VPN market is a classic trust-and-assurance product category: differentiation is often less about raw cryptography (most protocols are well understood) and more about operational discipline, governance, and verifiability.

Endpoint security still matters

If your device is compromised, a VPN cannot save you from:

- Keyloggers capturing credentials before encryption occurs.

- Malware exfiltrating data through the VPN tunnel.

- Session hijacking at the browser/app layer due to stolen cookies or tokens.

Think of a VPN as transport protection and routing control—not a full security stack.

Performance, latency, and bottlenecks

VPN performance depends on:

- Distance to server: more physical distance usually means higher latency.

- Server load and capacity: congested servers add delay and reduce throughput.

- Protocol overhead: encryption and encapsulation add computational work and extra bytes.

- Network path quality: sometimes a VPN improves stability by choosing a better route; sometimes it worsens it by adding hops.

The right expectation is not “VPNs are always slower” but “VPNs trade routing control and privacy for overhead; results vary by path, provider, and location.”

Common use cases and the best VPN pattern for each

Remote work and corporate access

For remote work, VPNs are often used to reach internal systems—file servers, admin consoles, staging environments, and legacy apps not designed for internet exposure. In enterprise architecture, IPsec gateways and policy-driven configurations are common; NIST’s IPsec VPN guidance focuses heavily on deployment policy, controls, and tunnel termination design.

- Best pattern: full-tunnel or app-specific split tunneling depending on policy, plus MFA and device security controls.

- Management insight: VPNs are often a transitional technology as organizations move toward Zero Trust Network Access (ZTNA), where access is more granular than “on the network = trusted.” Cloudflare, for example, publishes design guidance on migrating from VPN concentrators toward Zero Trust approaches.

Travel, hotel Wi-Fi, and airports

Travel is the simplest “yes, use a VPN” scenario because your network is unknown and often shared. The value is not theoretical—risk is practical:

- Open networks invite passive monitoring attempts.

- Captive portals and lookalike SSIDs increase phishing risk.

- Some hotel networks are misconfigured or poorly segmented.

A VPN can’t stop you from entering credentials into a fake login page, but it can reduce the chance that routine background traffic is exposed or manipulated.

Privacy from ISPs and local networks

If your goal is to reduce ISP-level visibility into your browsing patterns:

- A VPN hides the contents of traffic from the ISP (the ISP sees encrypted traffic to the VPN provider).

- The VPN provider becomes the entity that can see your traffic leaving the VPN server toward destinations.

This is a trade: you’re not eliminating trust, you’re changing who you trust.

Censorship circumvention and high-risk environments

In restrictive environments, VPN usage can be extremely high because users need it to reach blocked services. Reporting has described very high VPN reliance in Iran for bypassing censorship, illustrating how VPNs become infrastructure for everyday digital life under filtering regimes.

- Best pattern: use reputable providers, prefer modern protocols, and consider obfuscation if VPN traffic is actively blocked.

- Risk note: fake VPN apps and untrusted providers are a real threat in high-demand regions; security is as much about provider integrity as encryption strength.

Site-to-site networking for organizations

Site-to-site VPNs connect networks (office-to-cloud, branch-to-HQ) rather than individual laptops. This is where IPsec is especially common in standards-driven environments. Key design choices include:

- Topology: hub-and-spoke vs mesh.

- Segmentation: which subnets can talk to which (least privilege at the network layer).

- Monitoring: visibility at tunnel endpoints, and whether security tooling can inspect traffic where appropriate.

NIST’s IPsec VPN guidance includes operational considerations like tunnel termination and required monitoring controls.

Practical checklist: how to use VPNs safely

Kill switch, split tunneling, and always-on mode

Three client features can radically change real-world safety:

- Kill switch: blocks traffic if the VPN drops, preventing accidental exposure. This is especially valuable on unstable networks.

- Always-on VPN: automatically reconnects and enforces policy—useful for corporate devices and frequent travelers.

- Split tunneling: can be helpful, but increases complexity. Use it only when you have a clear reason (e.g., corporate app access while local printing stays local).

DNS settings and leak prevention

To reduce DNS and routing leaks:

- Use VPN-provided DNS resolvers (or your organization’s resolvers) routed through the tunnel.

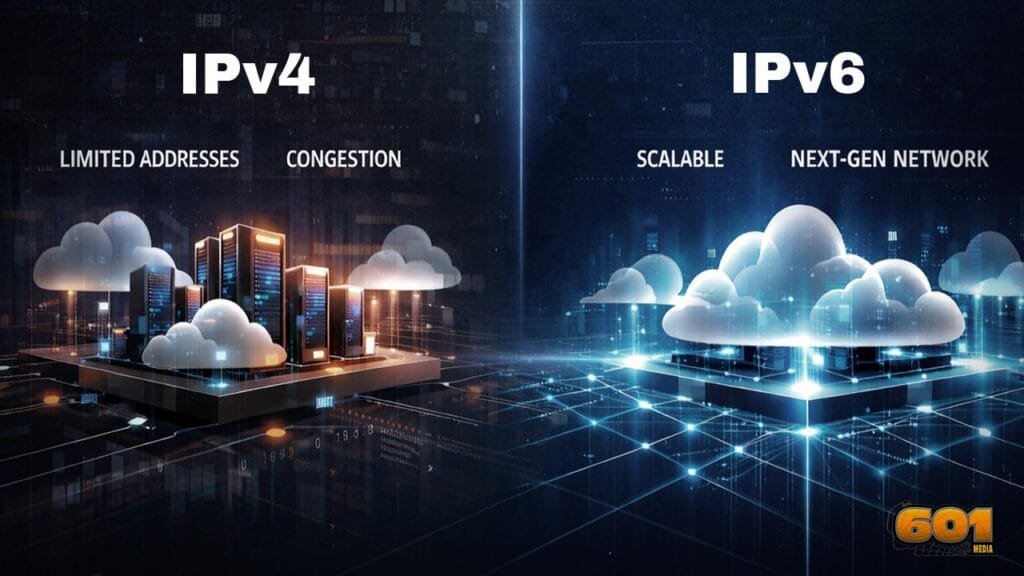

- Verify IPv6 behavior; if your VPN doesn’t support IPv6 properly, you may need to disable IPv6 or choose a provider that handles it correctly.

- Be cautious with custom DNS apps and “privacy DNS” settings that might override VPN DNS.

Corporate controls: MFA, device posture, least privilege

For organizations, the VPN is only one control in a broader access strategy:

- MFA: reduces risk of credential-based compromise.

- Device posture checks: block access from unmanaged or noncompliant devices.

- Least privilege: limit what VPN-connected users can reach; do not treat “connected to VPN” as “trusted for everything.”

- Logging and detection: monitor authentication, unusual access patterns, and lateral movement attempts at tunnel termination points.

Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Final Thoughts

The most important takeaway is that a VPN is a transport and trust-control technology, not a blanket privacy promise. Technically, it excels at one job: creating an encrypted tunnel that reduces exposure on untrusted networks and shifts the visible “origin” of your traffic to a VPN server. Strategically, it changes your risk posture by moving trust from the local network and ISP to a VPN provider (or your organization’s VPN gateway).

In Innovation and Technology Management terms, the winning VPN strategy is less about chasing buzzwords and more about aligning controls to real threats: choose a protocol and deployment model that fits your environment, harden the client settings to prevent accidental leaks, and treat provider selection as a governance decision. If you do those three things—threat-model, harden, and govern—you get the real security value VPNs can offer, without the false confidence that causes people to take unnecessary risks.

Resources

- NIST – Guide to IPsec VPNs (SP 800-77 Rev. 1)

- NIST – Guide to IPsec VPNs (publication landing page)

- WireGuard – Official site (cryptography overview)

- WireGuard – Paper (“Next Generation Kernel Network Tunnel”)

- OpenVPN – Cryptographic Layer (community docs)

- NIST – TLS guidelines (SP 800-52 Rev. 2 landing page)

- OWASP – Manipulator-in-the-middle attack overview

- OWASP – HSTS cheat sheet (HTTPS enforcement concept)

- Security.org – 2025 VPN consumer report (usage data context)

I am a huge enthusiast for Computers, AI, SEO-SEM, VFX, and Digital Audio-Graphics-Video. I’m a digital entrepreneur since 1992. Articles include AI assisted research. Always Keep Learning! Notice: All content is published for educational and entertainment purposes only. NOT LIFE, HEALTH, SURVIVAL, FINANCIAL, BUSINESS, LEGAL OR ANY OTHER ADVICE. Learn more about Mark Mayo