Explaining the TCP/IP Packet Life Cycle

A TCP/IP packet does not simply move from one computer to another. It is created, wrapped, addressed, transmitted, routed, verified, acknowledged, and finally reassembled. Understanding this life cycle is essential for anyone working in networking, cloud infrastructure, cybersecurity, or modern software systems.

Table of Contents

- Understanding the TCP/IP Model

- Application Data Creation

- Encapsulation and Packet Formation

- Packet Transmission Across the Network

- Routing and Forwarding Decisions

- Error Detection and Flow Control

- Packet Reassembly and Delivery

- Performance, Latency, and Optimization

- Security Implications of the Packet Life Cycle

- Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts

- Resources

Understanding the TCP/IP Model

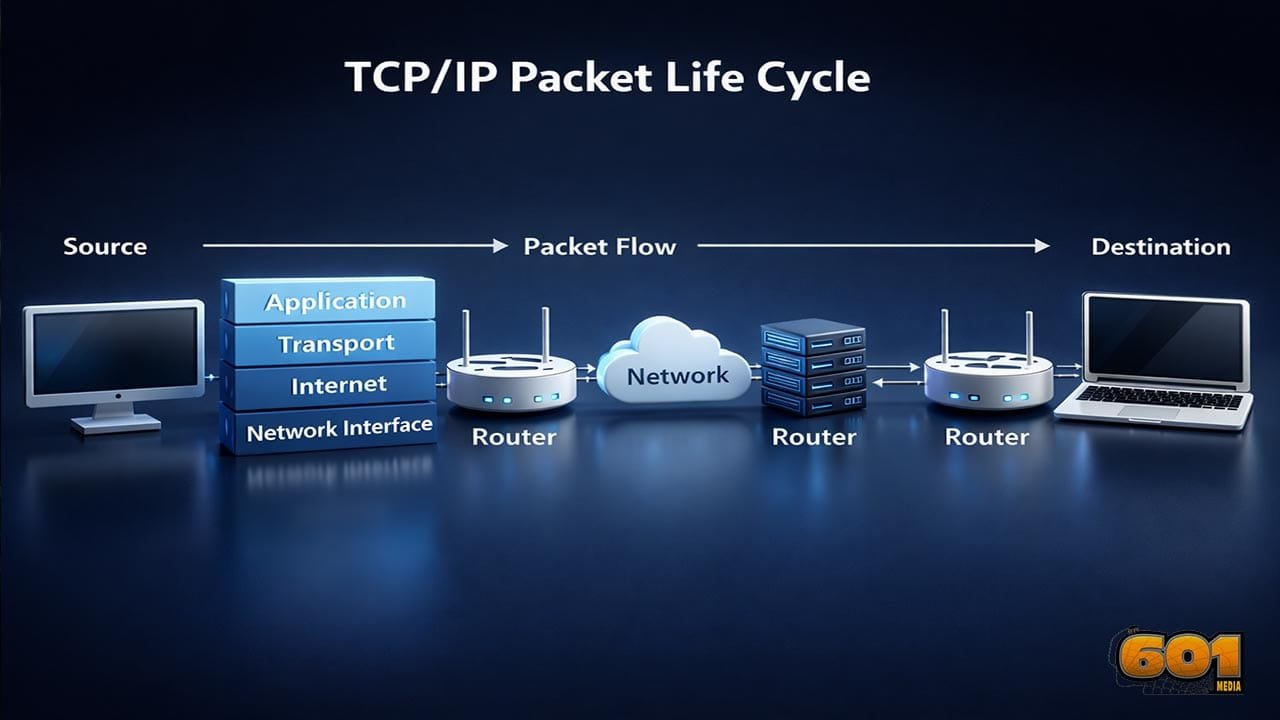

TCP/IP is the foundational communication model of the internet. It defines how data is structured, transmitted, routed, and received across heterogeneous networks. Unlike the OSI model, which is conceptual, TCP/IP is operational and implemented in real-world systems. The model consists of four layers: Application, Transport, Internet, and Network Interface. Each layer has a distinct responsibility, and together they form a pipeline through which data becomes a packet, travels across networks, and is reconstructed at the destination. The packet life cycle begins the moment an application generates data and ends when that data is successfully delivered to a receiving application.

Application Data Creation

The packet life cycle starts at the Application layer. This is where user-facing software such as browsers, email clients, APIs, and databases generate raw data. At this stage, the data has no awareness of networks, addresses, or transmission rules. Protocols such as HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, SMTP, and DNS define how applications format requests and responses. For example, an HTTP request includes headers, methods, and payloads, but it does not yet contain IP addresses or port numbers. The application hands this data to the Transport layer with instructions on reliability, ordering, and session behavior.

Encapsulation and Packet Formation

Encapsulation is the process of wrapping application data with protocol-specific headers as it moves down the TCP/IP stack. At the Transport layer, TCP or UDP is applied. TCP segments the data, assigns sequence numbers, and prepares acknowledgment mechanisms. UDP, by contrast, sends datagrams without guarantees, prioritizing speed over reliability. The Internet layer then encapsulates the segment into an IP packet. This adds source and destination IP addresses, enabling global routing. The packet is now uniquely identifiable and routable across interconnected networks. Finally, the Network Interface layer frames the packet for physical transmission. Ethernet headers, MAC addresses, and error-checking fields are added. At this point, the packet is ready to leave the host system.

Packet Transmission Across the Network

Once encapsulated, the packet is transmitted as electrical signals, light pulses, or radio waves depending on the medium. This could be copper cables, fiber optics, or wireless links. Transmission is not a direct path. The packet moves hop by hop through switches, routers, and gateways. Each device reads only the information relevant to its role, preserving abstraction between layers. Latency, bandwidth, and congestion all influence how quickly the packet progresses. Modern networks dynamically adjust transmission rates to optimize throughput and minimize packet loss.

Routing and Forwarding Decisions

Routing is the intelligence of the packet life cycle. Routers inspect the destination IP address and consult routing tables to determine the next hop. Routing protocols such as BGP, OSPF, and IS-IS continuously exchange topology information to adapt to failures and congestion. This ensures packets can find alternate paths if a link becomes unavailable. Importantly, packets from the same data stream may take different routes and still arrive successfully. TCP handles reordering and loss recovery at the destination.

Error Detection and Flow Control

TCP provides reliability through acknowledgments, retransmissions, and congestion control algorithms. If a packet is lost or corrupted, the sender is notified and resends the missing data. Checksums detect transmission errors, while sliding window mechanisms regulate how much data can be in transit at once. This prevents overwhelming slower receivers or congested networks. UDP, on the other hand, relies on application-level logic for error handling, which is why it is favored for real-time services like video streaming and online gaming.

Packet Reassembly and Delivery

When packets arrive at the destination host, the process reverses. The Network Interface layer removes framing, the Internet layer validates IP headers, and the Transport layer reassembles segments into a coherent data stream. TCP ensures correct ordering and completeness before passing the data upward. Once verified, the original application data is delivered to the receiving software exactly as it was sent. At this point, the packet life cycle is complete. The application processes the data and may generate a response, starting the cycle again in the opposite direction.

Performance, Latency, and Optimization

The efficiency of the packet life cycle directly affects application performance. High latency, packet loss, or jitter can degrade user experience and system reliability. Techniques such as window scaling, selective acknowledgments, and congestion avoidance algorithms like CUBIC improve TCP performance over high-speed networks. Content delivery networks, load balancers, and edge computing architectures optimize packet paths by reducing physical distance and routing complexity.

Security Implications of the Packet Life Cycle

Every stage of the packet life cycle presents potential attack surfaces. Packet sniffing, spoofing, man-in-the-middle attacks, and denial-of-service exploits all target weaknesses in transmission and routing. Encryption protocols such as TLS protect application data, while IPsec secures packets at the Internet layer. Firewalls and intrusion detection systems inspect packet headers and payloads to enforce security policies. A deep understanding of packet behavior is essential for designing secure, resilient systems in modern networked environments.

Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Final Thoughts

The TCP/IP packet life cycle is the invisible engine of the digital world. Every click, message, and transaction depends on this precise choreography of encapsulation, transmission, routing, and reassembly. Mastering this process provides deep insight into performance tuning, fault diagnosis, and secure system design. In an era defined by distributed systems and cloud-native architectures, understanding how packets live and move is no longer optional. It is foundational.

Resources

- RFC 791 – Internet Protocol Specification

- RFC 793 – Transmission Control Protocol

- Computer Networking: A Top-Down Approach by Kurose and Ross

- Cisco Networking Academy Documentation

I am a huge enthusiast for Computers, AI, SEO-SEM, VFX, and Digital Audio-Graphics-Video. I’m a digital entrepreneur since 1992. Articles include AI assisted research. Always Keep Learning! Notice: All content is published for educational and entertainment purposes only. NOT LIFE, HEALTH, SURVIVAL, FINANCIAL, BUSINESS, LEGAL OR ANY OTHER ADVICE. Learn more about Mark Mayo